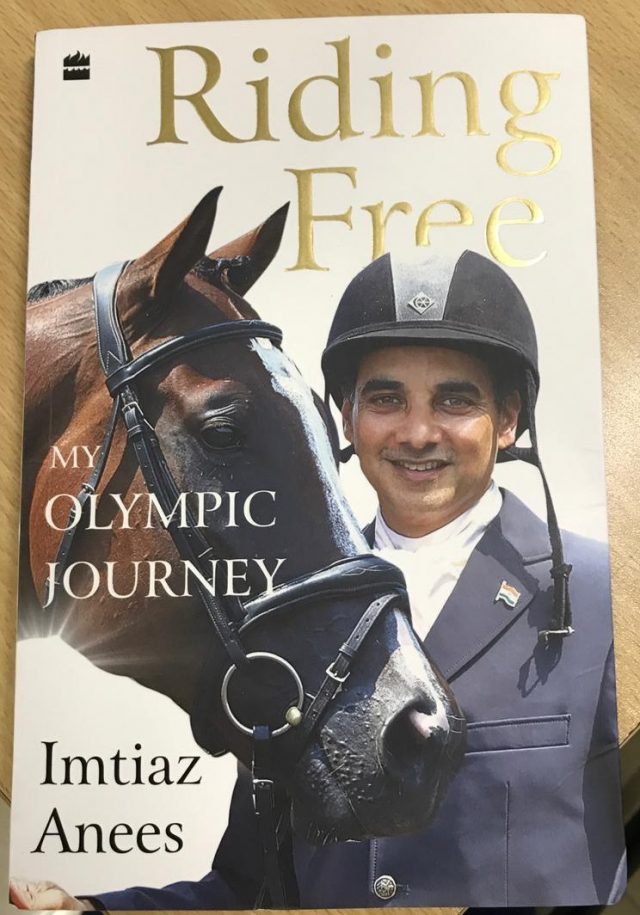

Author: Imtiaz Anees

Publisher: Harper Collins India

Price: Rs 299

Pages: 161

Getting to the Olympics is every sportsperson dream. Olympian Imtiaz Anees harboured the same dream as a boy when he first learnt to ride a horse and got captivated by the lure of being on a horseback. In his recently published autobiography, Imtiaz has tried to tell his story in simple words. Throughout the book, he has impeccably maintained the tone and tenor of the narration to childlike enthusiasm. it is no doubt very easy read and fast-paced.

There are some flaws nonetheless.

In a hurry to bring out the book before this year’s Tokyo Olympics opened. The publishers’ Harper Collins India made a sheer cardinal mistake, which Imtiaz himself was unaware of till it was pointed out to him.

The book starts abruptly. There is no introduction to the subject. No Foreword. Come on! A discipline as complex as equestrian, it’s not horse racing, which is a straightforward sport. The discipline in equestrian that Imtiaz finally gets attached to—Eventing. It is not a verb. Eventing is a proper noun in equestrian parlance. The book certainly needed a foreword, either from a fellow equestrian practitioner, or from one of his teammates when he represented India at the Asian Games in Bangkok in 1998 and won the bronze medal. It wouldn’t have been a tough task to convince a soul of authority in the sport of equestrian to write a foreword. The topic needed a small introduction because this is not a sport that one watches so often. In fact, one hears about equestrian only once in four years when Olympics or Asian games come along.

In the first chapter—Starting young: Paradise lies on horseback—Imtiaz has put his heart out. The beginning is so captivating and as one reads on this story gets interesting, the struggles he faces in getting to where he wanted to despite coming from a privileged background, is fascinating. His narration of his early days in Lawrence School Sanawar—to be away from family and staying in a boarding school. Brought alive the memories of early school days.

“At long last we finally reached Sanawar and as we entered the gates of the school, I finally accepted that there was no going back and there were no parents waiting for me at the end of the two-and-a-half-day journey. “Writes Imtiaz.

His every effort to get thrown out of the school, coax his grandmom to intervene and convince his parents to get him back to his hometown Mumbai, makes an interesting reading. In the later part, he agrees that years at the boarding school hardened him to face life in whatever situation he would be in future—there were several such occasions as he prepared to achieve his quest to be an Olympian.

There comes a situation during his journey towards achieving India colours wherein he had to achieve certain points in the given time frame to be able to make it to the Indian team for the 1994 Asian Games in Hiroshima. Before the last trial to be held in Delhi, Imtiaz was in third place among the stakeholders. After he had gone through four trials. there was no confirmation of his place in the team because he had missed one trial due to injury, so had lost out on scoring points.

Finally, when the team was announced by the EFI, he had made it. Imtiaz became the first civilian to make it to the Indian equestrian team. More good luck followed when the Sports Authority of India decided to send the dressage team to France for a month-long training before the Asian Games. The training was to be done at Cadre Noir, the world’s best classical dressage training school. this was a chance for which any equestrian athlete would die for.

“It was unbelievable that I was training with the Cadre Noir. I Had only read about them in books and seen their pictures—immaculately dressed instructors in their trademark black uniforms. Not even in my wildest dreams about my future did I think that I would set foot in these hallowed grounds” says Imtiaz. After France training, he went on to train in Switzerland with the Swiss National coach, who had invited him to stay with him during his many visits to Delhi as trainer of the Army team.

Imtiaz returned to India to get kitted. Nothing could replace the happiness of wearing a blue Indian blazer. But shocks were in store for him at every corner. A few days before he was ready to travel with the Indian contingent. A newspaper report about the Indian team travelling to Hiroshima did not have his name. instead, the EFI had included an Army officer.

“At first, I thought this was ridiculous—it couldn’t be happening. Then I was angry at such injustice. Not a word had been said about why I had been dropped.” Is how he describing in the book? When I asked him to elaborate, he simply said “The point wasn’t about why I was dropped it was about how to recover from setbacks and not give up your dream, I wrote this book for a much larger audience focussing on living your dream and not giving in.

A rather critical assessment of the situation was necessary. For far too long the Army-controlled EFI HAS been having its way without giving any reasons.

My quest to find an answer led me to Major Rajesh Pattu (retd.), who was Imtiaz’s teammate four years later at 1998 Asian Games in Bangkok, where the two became bronze medallists.

Maj Pattu was much open about the functioning of the EFI.

“Selection of the Asian Games is always in controversy because it is not done in a transparent way. I too was removed in 2010 Asian games by the federation by saying that my horse had tick fever. They did not give me the report and nor agreed to do one more test. I am convinced that it was done only to remove me from the team.”

In the last Asian games too, I was dropped after being selected on merit because another rider had to be accommodated in the team.

“Equestrian Federation has always got themselves involved in controversies because they don’t have any systems in place. Importance is not given to the best team for India but to who all should be on the team,” says Maj. Pattu:

In 1991, Imtiaz and me represented the country in Australia. Since then, I have been competing. Have represented India in three Asian games and each time won a medal (1998, 2002, 2006)

I was Dropped in 2010, the horse became unfit in 2014 and was selected but dropped in 2018 because of politics in the federation.”

I wanted to retire in 2018 but just because of the federations wrongdoing doing now I want to compete in the next three Asian Games. Just to prove a point …. Not to them but to myself,” says Maj Pattu.

Such frankness is called for when a sportsperson writes an autobiography. Because it is a platform one should open up which is denied when you are in country colours. Imtiaz is certainly not an inspirational guru to think that his book would give inspiration to the young and aspiring lot to achieve their dreams. No wonder the publishers have inserted a critical line on the copyright page.

The publishers have refused to take responsibility for the facts reported by Imtiaz in the book. It actually downgrades the entire content. That’s why I said foreword was necessary. Apparently, his family and friends were inspired by his story—from his early rides to finally when he makes it to the 2000 Sydney Olympics— pushed him to write this book, which at the outset looks to be a paid for book. Harper Collins certainly wouldn’t commission an autobiography to an obscure and retired sportsperson. And by the time this book was still printing. He wasn’t the only Equestrian Olympian in India, as claimed on the back flap cover of the book. Fouaad Mirza had qualified for Tokyo Olympics on merit, without the fuss Imtiaz had to go through to his Sydney qualification. Mirza, for the record, made it to the individual Eventing jumping final in Tokyo and finished in much better placing than Imtiaz did way back in 2000.

Names of horses always make funny reading. Psychic Force, Wizard Of Stocks, Victorious Sermon, My Opinion, Cosmic Ray, Northern Alliance, to name a few.

In the first chapter Starting Young: paradise lies on horseback, where Imtiaz describes his thoughts of starting at the 2000 Sydney Olympics. He mentions 6-5-4-3 the countdown continued………! Spring Invader, leapt forward on cue and we were thundering down the course in the final chapters dedicated to Sydney Olympics, he has clearly mentioned it was Kevin that he rode in Olympics?

Imtiaz’s response was “Spring Invader and Kevin are the same horse. I had no patience to go through the book again to find the text where he mentioned Kevin was named Spring Invader. it reminds me of Shakespeare’s masterpiece Romeo and Juliet “what’s there in a name”. Romeo and Juliet could very well be a name of a horse in one of the many stables in India.

There are more instances like on page 111 where he talks about the Indian team winning a bronze medal at the 1998 Asian games in Bangkok—he writes that as the Indian National Anthem played out across the stadium as the Indian flag went up, I felt emotions that are hard to describe –immense happiness……..

How can this happen? National Anthem is played only for the gold medal-winning country and that country’s flag, which is in the middle sandwiched between the flags of silver and bronze winners.

To which Imtiaz says “Yes you are right, I may have said it in a wrong manner what I meant was you get goosebumps when a National Anthem plays even though it is of another country you see the flag going up and in my mind, I was singing the Indian National Anthem.” I believe This languid mistake wouldn’t have happened but for the writer Sherna Gandhi, who seemingly has little knowledge of sports. Had Imtiaz taken a sports journalist to write his book, such a silly mistake would have been pointed out immediately.